War is a thing of terror, traditions, heartache and often, boredom. Passing the time between patrols, and the banality that comes from life in the field, is a constant challenge. Some people read. Most exercise. Everyone complains about the food. Soldiers write, train and call home--if there's someone there that'll pick up the phone. Video games? Totally a thing, in some instances. If you have a Sharpie, or a knife, there's a good chance that you might wind up doodling, scratching or scrawling something, at one point or another, to prove that you were there, where ever ‘there’ might be. Jonathan Bratt, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan and a current company commander in the National Guard, put together a great read on the history of military graffiti for The New York Times. Starting with 5,000-year old cave paintings and navigating conflicts across the span of history, Bratten touches on the artwork and vandalization that soldiers, living in Death’s shadow, undertook to cure themselves of boredom and, in some cases, serve as proof of their existence. From the

New York Times Magazine:

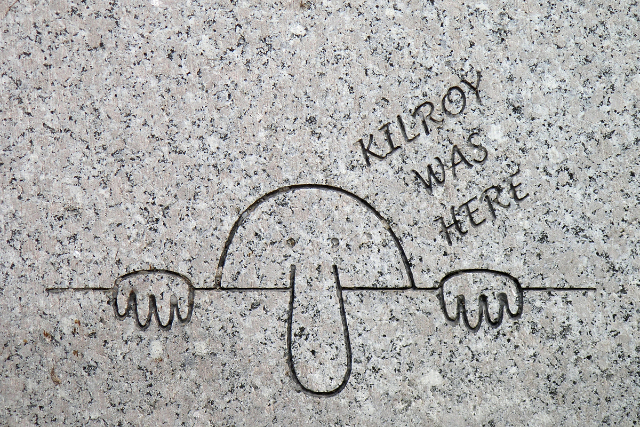

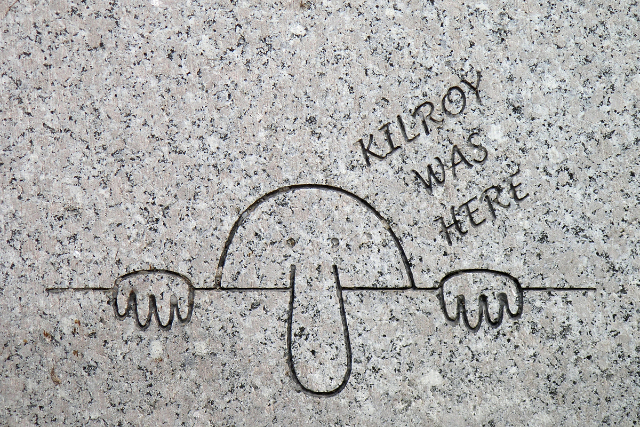

World War II brought U.S. troops to Europe by the millions, and this time they were accompanied by a friend: Kilroy. Kilroy was a mysterious phantom, asserting his presence in the scrawled phrase “Kilroy was here,” often accompanied by a cartoon doodle of a bald head just peeking over a wall, nose and fingers visible. And Kilroy was everywhere. Troops claimed that when they’d storm a beach or take a village, they’d somehow find that Kilroy had gotten there before them. One story goes that Stalin came back from the bathroom at the 1945 Potsdam Conference demanding to know who Kilroy was; sure enough, some enterprising G.I. had tagged the bathroom. Just what the appeal of Kilroy was we’ll never quite know, which is perhaps the greatest example of a military-wide inside joke.

It’s a great read, full of humor, sadness and thoughts on the impermanence of life--that's a lot to ask from a feature on graffiti.

Image via Wikipedia Commons